Nikita and his wife, Oksana, fled Russia in desperation two years ago, believing America was their only hope of giving their three children a life free of fear and oppression.

Instead, those children are growing up behind the razor-wire fences of a South Texas detention center, among hundreds of other families swept up in President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown.

Over their four months at the Dilley Immigration Processing Center — a remote, prisonlike facility that has drawn mounting scrutiny over what human rights advocates describe as inhumane conditions — Nikita and Oksana say their children have endured indignities they never imagined possible in the United States.

Worms in their food. Guards shouting orders and snatching toys from small hands. Restless nights under fluorescent lights that never fully go dark. Hours in line for a single pill.

“We left one tyranny and came to another kind of tyranny,” Nikita said in Russian. “Even in Russia, they don’t treat children like this.”

NBC News spoke with the family over Zoom this week and reviewed their lawyer’s request for their release, as well as dozens of pages of medical records. For an hour and a half on the video call, Nikita, an engineer, and Oksana, a nurse, described how their months at Dilley have worn down their children — physically, emotionally and academically. Their two oldest sat behind them in a drab conference room, doodling or staring blankly at the screen. The preschooler wandered the room, swinging a thin plastic rod from a set of window blinds like a toy sword.

The couple asked to be identified only by their first names because they fear retaliation if deported back to Russia, where Nikita says he spoke out against President Vladimir Putin’s regime.

Their story offers a glimpse of what children are enduring in prolonged confinement as the Trump administration expands family detention.

Kirill, 13, who once taught himself to play piano and attended music school, spends most days withdrawn, waking at night with anxiety and panic attacks, his parents said.

Konstantin, 4, a sociable boy, is often frightened by loud noises and guards, his parents said. He once cried for hours after a small toy airplane was confiscated.

Kamilla, 12 — a dancer who loved to perform — now has partial hearing loss in one ear after what her parents say was a poorly treated infection. For weeks, she counted down the days until her birthday, telling NBC News she had only one wish.

“To get out of here,” she said.

On Monday, the family’s attorney, Elora Mukherjee, filed a request for their immediate release on medical grounds. In the letter, Mukherjee, a Columbia Law School professor and director of its Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, wrote that the children had been detained for more than 120 days, more than six times the 20-day limit set in a federal court agreement governing the detention of minors. She argued that their health has deteriorated as a result.

“Kamilla should not be spending her birthday in prison,” Mukherjee said. “She has done nothing wrong.”

In a statement, the Department of Homeland Security defended holding the family while their asylum case is pending. It said the Dilley facility “is retrofitted for families” to ensure children’s well-being and accused the media of “peddling hoaxes” about poor conditions in immigrant detention centers.

“The Trump administration is not going to ignore the rule of law or release unvetted illegal aliens into the country,” the statement said. “All of their claims will be heard by an immigration judge and they will receive full due process.”

CoreCivic, the company that operates Dilley under a federal contract, has deferred questions about the facility to DHS and said in statements that the health and safety of detainees is its top priority.

The family’s detention comes as Trump immigration officials revive and expand large-scale family confinement. Past presidents used family detention in limited circumstances, and the Biden administration largely halted the practice, releasing most asylum-seeking families while their cases moved forward. Under Trump, authorities are sending families to Dilley in significant numbers and reportedly holding them for weeks or months.

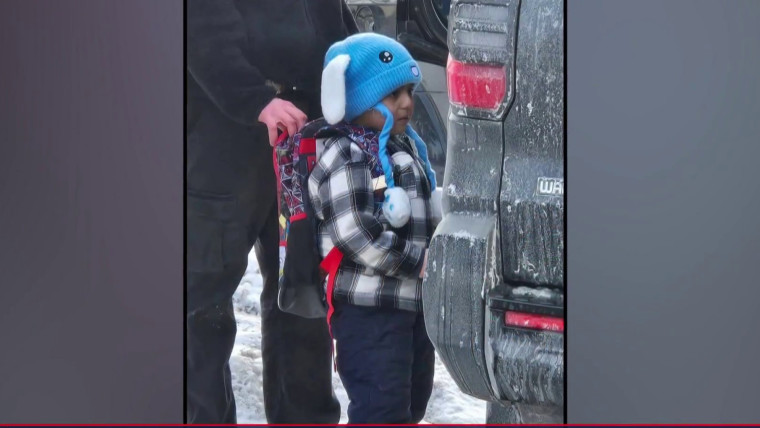

The facility drew widespread national attention last month after a photograph of 5-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos, wearing a blue bunny hat as he was led away by officers, spread online, renewing concerns about conditions inside Dilley. Since last spring, lawyers and advocates have complained of inadequate medical care, contaminated food and minimal schooling for children held there.

DHS has said family detention is necessary to keep families together while it works to deport them.

Nikita and Oksana’s journey to Dilley began in October. After fleeing Russia in 2024 and spending more than a year in Mexico trying to determine the best path to safety in the U.S., Nikita drove his family to the Otay Mesa port of entry and requested asylum, telling an agent that his activism against the Russian government had put them at risk. An asylum officer later found the family had a credible fear of persecution, according to Mukherjee. But rather than being released into the U.S. while their case moved forward, they were taken into custody.

After five days in frigid federal holding cells — where the family says the children slept under foil blankets on thin mats — they were transferred to Dilley, expecting to wait there for a couple weeks at most.

Their plight reflects what advocates describe as an impossible choice facing many Russian asylum-seekers. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, anti-war activists, online critics and military draft resisters fled the country by the tens of thousands, fearing imprisonment or worse. With Europe largely closed to Russian nationals, many turned to the U.S. southern border as one of the few remaining paths to protection, believing America would be “a safe harbor for those who strive for freedom and democracy,” said Dmitry Valuev, president of Russian America for Democracy in Russia, a group that has advocated for Russians trapped in U.S. immigration centers.

Instead, Valuev said, some now find themselves detained indefinitely.

“And they don’t understand what for, because they are not criminals,” Valuev said. “They came to the United States to contribute to society, to their new home. They don’t want to become illegal immigrants. They want to obey the law.”

Inside Dilley, Nikita and Oksana said, the days blur together.